For this inaugural Sunhouse blog post, we want to address a topic that drives our design approach and that is really central to the state of music creation today: the relationship between human action and sound creation. This may sound abstract, but with the widespread and growing use of electronic instruments in both production and live performance, we wonder: How and why have keyboards, knobs, pedals and buttons become our primary means of performing with electronic sounds? Whether you're using keyboard synths, MPCs, V-Drums or any other MIDI controller, you're pushing buttons, twisting knobs and adjusting sliders, which, compared with our rich history of acoustic instrument practices, is more like operating machinery than playing music. And more importantly, we're interested in whether there is a better way.

Since time immemorial, we've been striking, strumming, rubbing and blowing on physical objects to create music. Over millennia, we've designed drums, violins, horns and thousands of other instruments with increasing technological precision, but what they all have in common is the inextricable relationship of their physical characteristics to how they sound and are played. A silver flute sounds different than a brass one, a drum hit with a wooden mallet different from one hit with a metal one. Makes sense.

But with the advent of electronics and the computing age, the relationship between physical gesture, material and sound creation was effectively severed. The invention of the electronic oscillator allowed us to create musical tones by expending electric energy rather than human energy. With the oscillator, sound is determined by circuit architecture, not hitting or rubbing something, so explicit interfaces had to be designed for people to play these new “instruments.” But what would these interfaces be like?

In this new paradigm, there are no inherent reasons to do things one way or the other, and early electronic instrument design saw widely varying approaches. In the 1920's Leon Theremin created a truly unique instrument, the Theremin, that was more like acoustic instruments in that it was playable with human gestures (maybe the first instrument that could be played without touching anything). Hand distance to two metal poles controlled pitch and volume and musicians like Clara Rockmore mastered the instrument and created some striking and beautiful music. It was also used in a lot of '50s sci-fi movie sound tracks.

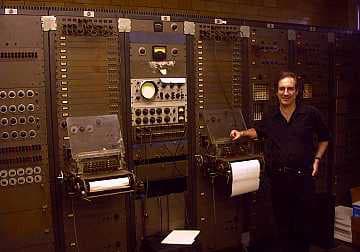

One of the first programmable synthesizer instruments, the RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer, which occupied an entire room and was operated by technicians, adopted the metaphor of the musical score and the conductor of a symphony for it's user interaction. Composers would write musical instructions using punch cards that would be read by the machine. Like other computers of its era, it was controlled with knobs and switches. It was thought at the time that this technology would replace large symphonies for recording musical pieces.

But electronic instruments were mostly niche until Robert Moog's keyboard synths successfully bridged classical performance practices with the world of electronic sound. He took a well known interface, the piano keyboard, and applied it to control electronic sounds. This opened up the western oeuvre of composition into the electronic age. Wendy Carlos' “Switched On Bach” album, where she played Bach on a Moog synth, was wildly successful.

The keyboard was an especially suitable metaphor for a few reasons. First, pianos are already an abstracted interface for hitting strings. You're not hitting the strings directly, but pressing a highly sensitive key that triggers a complex mechanism that hits the strings. You're not directly producing the sound like you are with a drum or guitar–there's a layer of abstraction in between that essentially standardizes and limits the kinds of sounds you can make (unless you reach into the piano and start messing around). This greatly simplified the technical aspects of recreating the instrument electronically. And second, there were already lots of pianos in homes and people that knew how to play them. So its no mystery why Moog's instruments surpassed more obscure approaches and went mainstream, spawning a slew of other companies designing keyboard synths.

Also, switches, knobs and pedals have always been a part of keyboard playing. Just look at the pedals on a grand piano or all the knobs and switches on an organ. Piano players are used to dealing with them, so extending them to other kinds of effects just made sense. Knobs and switches are also natural to the design of electronics. So knobs became the primary means of gestural input for electronic instruments, providing the only way of controlling continuous parameters. For keyboardists, being able to control the timbre, quality and envelope of each key stroke was an extension beyond what they could do with acoustic keyboards and these instruments spawned new genres and sounds by broadening what was sonically possible in performance. See: Mile Davis' 70's band, Disco, Electronic Music, etc.

At Sunhouse, and with our first endeavor Sensory Percussion, we're going back to basics, not just making new kinds of buttons and knobs, but working to digitize acoustic performance–physical gestures, expressive movements, manipulation of physical objects.

We are huge fans of electronic music and are excited with where music technologies have taken us, but this progress has taken a toll on performance and the place of instrumentalists in music. It has become a studio art. By rethinking our assumptions to electronic instrument design, we aim to bring the performer back into the conversation and allow for seamless interaction between that second nature interaction with physical objects and electronic music performance. You won't need knobs, switches and pedals to be expressive… you just play your instrument.